Let's Lie To Each Other For Fun

Deal with the Devil, designed by Matúš Kotry, is a eurogame for exactly four players about building up a medieval city. Players vie for resources, construct new buildings, and attempt to maintain favorable moral standing with the world’s citizens while avoiding the eye of the church’s inquisitors. Throughout the game, you’ll have a dearth of some resources and a surplus of others, and will need to deftly maneuver trades with the other players to succeed.

At the beginning of each round, players load up little cardboard chests with resources other players say they want and set a price for the whole lot. Once all the chests are loaded, they’re shuffled up, then scanned with a phone app which tells you who gets what chests. Everyone reviews the chest they got and either pays the price to get the goods or closes it without taking anything. Then they’re shuffled, distributed, and reviewed one more time before ultimately returning to their owner. The app handles the distribution of each chest using a qr code, so your chest remains anonymous the entire time; you have no real idea which players you actually did deals with.

There’s a catch to all this: one of the players is secretly the devil trying to purchase the souls of the living. Another player is a heretic trying desperately to repair their soul before the inquisition finds them out. The devil starts the game absolutely flush with resources, whereas the mortals start off quite poor. When it comes time to trade, the devil has plenty of gold on hand to purchase the resources offered up by the other players. The devil also has plenty of resources to put up for sale; unfortunately for the mortals, the only way to buy them is by handing over a piece of their soul.

At a couple points of the game, players get a chance to guess who they think the devil and cultist are. If they guess correctly, some game mechanics happen that ultimately lead to the devil losing points. Unlike other social deduction games, though, the game doesn’t revolve entirely around figuring out who the evilton is. If you’re playing a game of The Resistance and the good guys figure out exactly who all the bad guys are, they’re almost certain to win.

Since Deal with the Devil is a eurogame at heart, you win by collecting the most points and you primarily get points by building buildings and creating an efficient resource engine. The devil starts with a tremendous resource advantage, but will end up losing if they flaunt their wealth too hard and make it clear that they’re no mere mortal. In that way, the social deduction operates as just one more piece to the overall puzzle.

Roleplaying With A Hint of Social Deduction

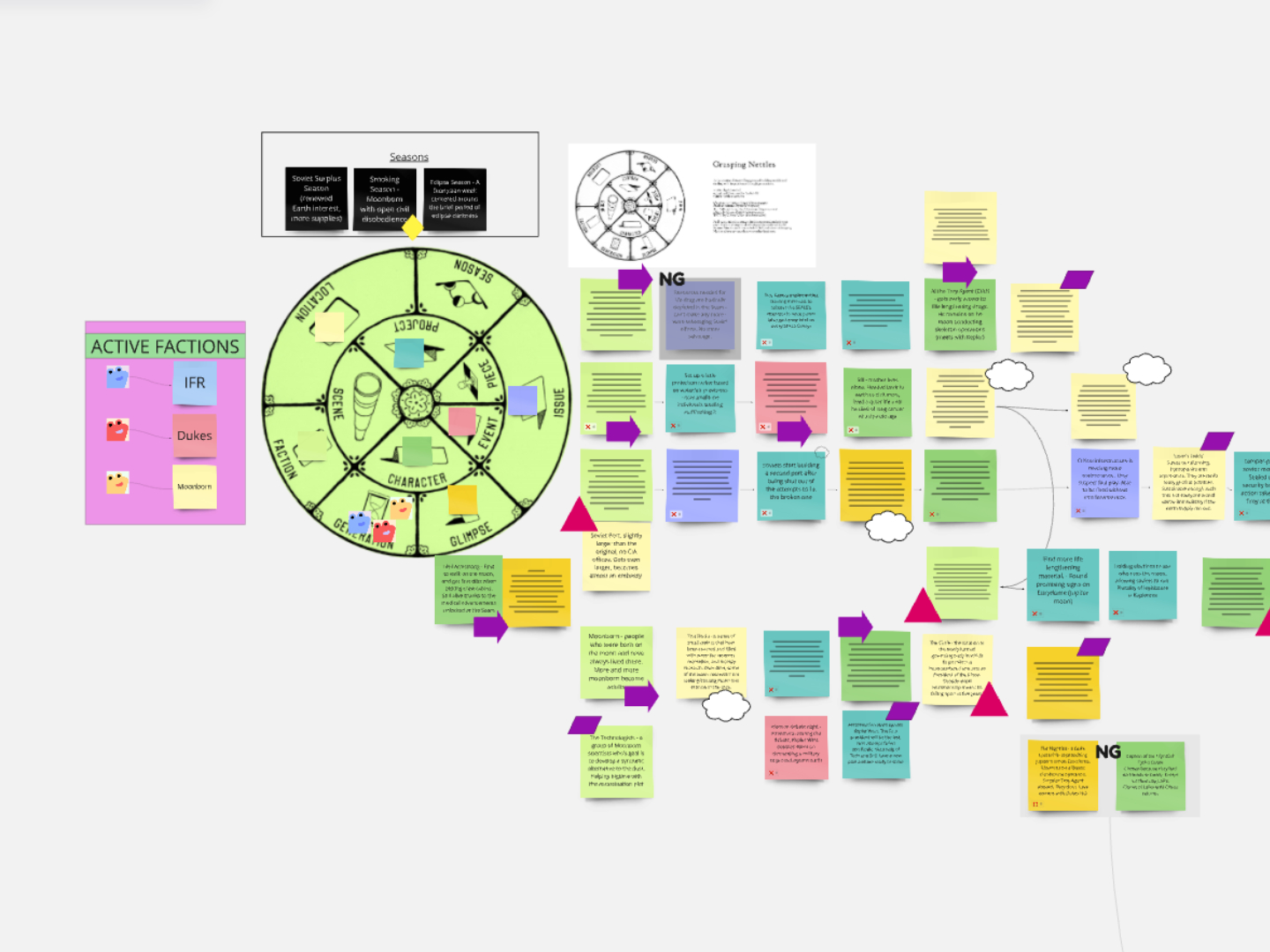

A few years back, I played a game of Grasping Nettles with some friends where we created a world in which the Apollo missions landed on the moon and stayed there, then an international moon base sprung up and not too long later the Troy Agency (basically, the space CIA) figured out how to crush specific moonrocks into a life-lengthening powder called the dust.

Like many games of Grasping Nettles, we ended up with a handful of story threads that were begging to be resolved in another roleplaying game. One of those threads led to my largely unremarked-upon sci-fi roleplaying game Promise the Moon. Another led to an extremely fun game of Follow, by Ben Robbins, where we hacked in a social deduction element that was an absolute blast in play. Follow is a game about overcoming the various challenges of a quest. Our game focused on the covert mission of the spaceship Nightfall, venturing off to the Jupiter region of our solar system to recover and hide a few caches of the ever-valuable dust. Unfortunately for the 5 person crew, one of them was secretly a member of the Troy Agency looking to claim the caches and sabotage the mission.

After creating characters, but before beginning the first scene, we randomly & secretly determined who the Troy spy was. We didn’t put in any additional mechanics: no secret win condition, no options for revealing someone’s loyalty, no special powers. We just let it hang there in the air between us, oozing tension into every scene which billowed out during each of Follow’s challenge resolution steps. The game is set up incredibly well for this type of play, since the core resolution mechanic takes into account if characters actually want their fellowship to succeed. It worked beautifully, and is still one of my favorite rpg sessions of all time.

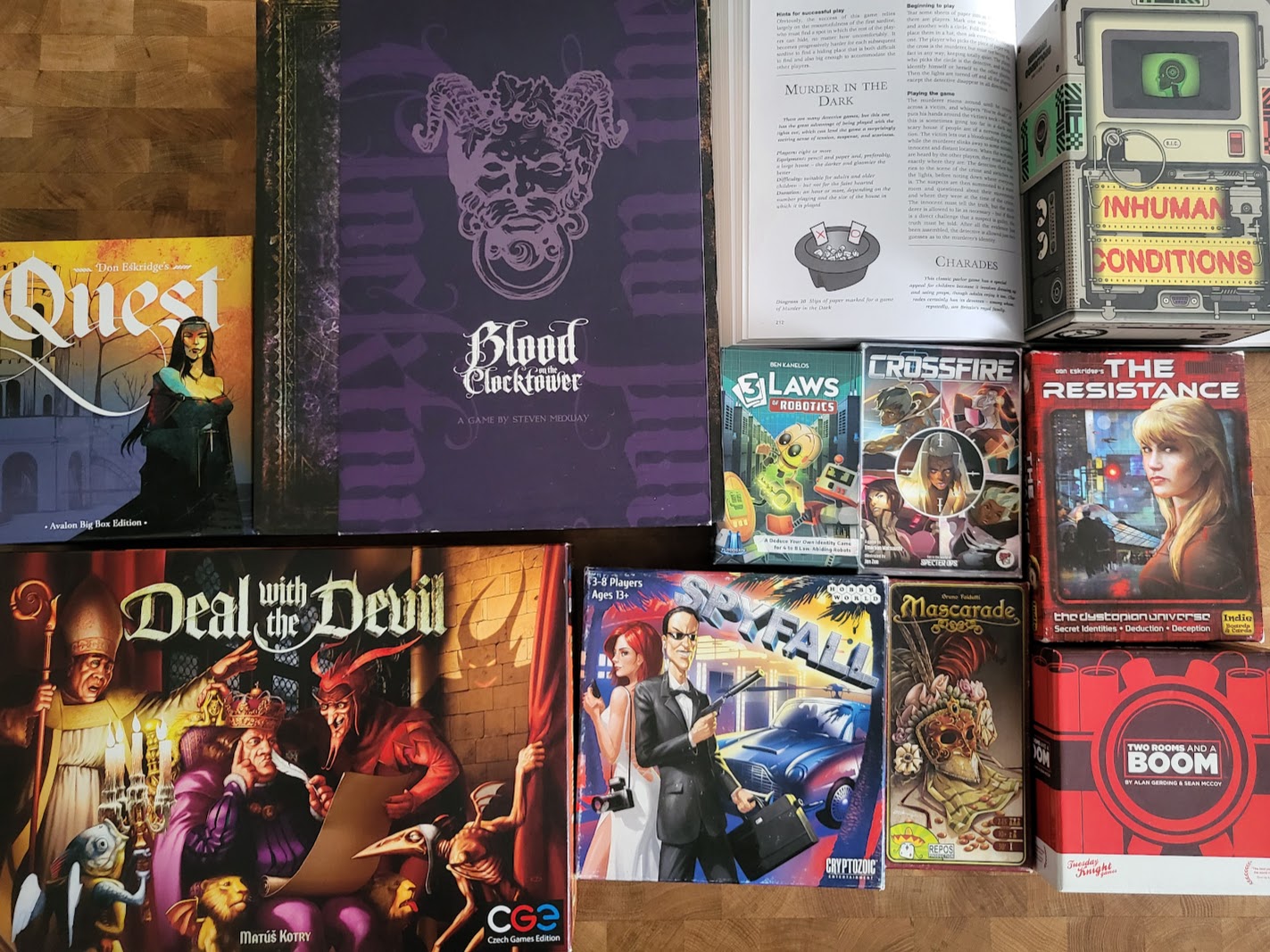

Why Do I Like Social Deduction

Pure social deduction is probably my favorite genre of game to play. Lying and deception are fascinating consequences of our thinking brains, but are pretty nasty forms of behavior in real-life social interactions. Social deduction games like The Resistance, Blood on the Clocktower, and Two Rooms and a Boom—three of my all time favorite games—provide a consensual sandbox for experimenting with these less-than-savory methods of social engagement. Players hop into the game armed with a social contract that lets them tell bald-faced lies right to each others’ faces within the context of the game. There might be some bleed into “real” feelings during play, but if we all commit to the game, we’ll still be friends once it’s over.

These games make a lot of people uncomfortable! That can make it quite hard to get any of them to the table; for the Resistance, you really want 6 or 7 sickos who are ready to dive all the way in. For Blood on the Clocktower and Two Rooms and a Boom, you’re hoping for at least 8 but up to 20 or 30!

Deal With the Devil requires exactly four people, and manages to alleviate some of that discomfort by decentering the hidden role element from the core gameplay loop and reward system. It’s still there, there’s still chances to lie and deceive, but most of it comes through the asynchronous and anonymous trading system and then manifests with players being suspicious of why someone was able to afford the buildings they constructed that turn. Deal With the Devil sheds light on some design space where roleplaying games can experiment with similar subsystems of social deduction that act as a garnish or side dish instead of the main course.

Three Ideas that Haunt the Walrus

This is Haunted Walrus, so of course I’m gonna end the article by pitching some game ideas to you. As always, feel free to steal these ideas and share your own in the comments!

Undercover God

I’m immediately bringing in another social deduction game for inspiration here in the form of Insider, designed by Team Insiderrrr and published by Oink games. Insider is basically a timed game of 20 questions: one player has a secret word that the other players have to ask yes or no questions to narrow down. One of the players on the guessing team is the “insider” and actually knows the answer, and thus has to invisibly guide their team towards getting it right. You can’t be too obvious though: if the guessing team gets the right answer, they have to single out the insider to actually win. It’s good fun and flips the normal social deduction script on its head; instead of a traitor, you have a secret helper that needs to remain anonymous to win.

Now imagine a group of adventurers on some mission from their god. Everyone plays a member of the party, grabs a character class with some abilities and suits up with swords and armor or whatever other thematically appropriate gear. Then, one of the players is chosen at random to secretly be the god that the party is on a mission from. The mission was simply too important to leave it to the mortals entirely, but they each have an important role to play in the coming mission. However, if they figure out their god is among them they’ll be insufferable with worship and the like, feeling like they’re blaspheming by sharing air with such a divine being, and all that business. That would jeopardize the mission, so the god prefers to stay incognito.

When it comes time to roll dice, players always roll their dice secretly and announce the result. The god player can announce whatever result they want; they’re not bound by fate or chance and thus will only fail when they want to appear human. Throughout the game, the non-god characters start to get tipped off that there’s a god in their midst and I think the whole thing would be a blast.

Skimming Off the Top

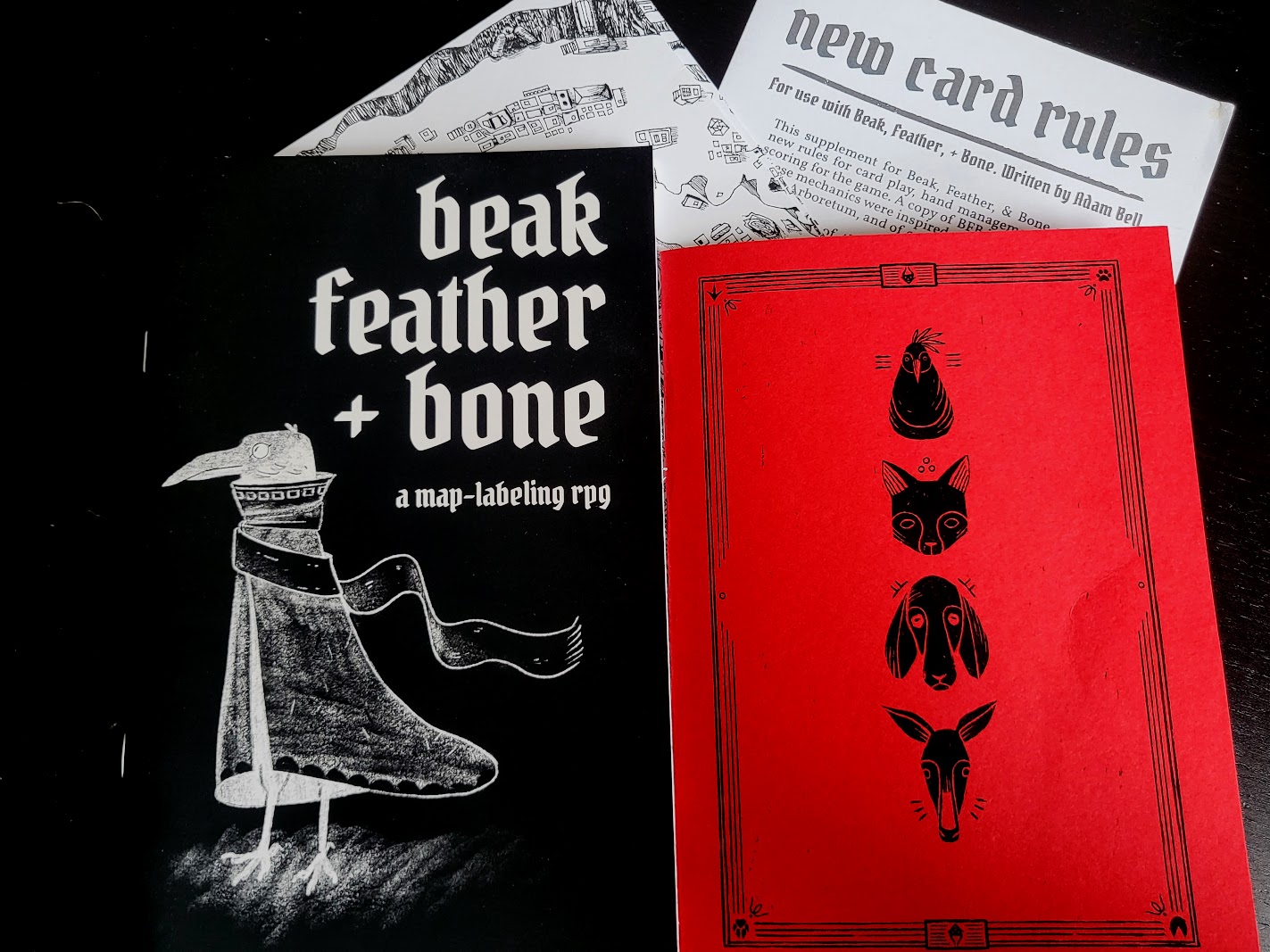

I like the idea of rpgs with a competitive element like Beak, Feather, and Bone and Last Train to Bremen. There’s something extremely fun about building a competitive atmosphere in a game where the main purpose is to tell a nice story.

You’re all running a protection racket; maybe it’s a scene-based game where you’re building out a map of your mafia’s influence by setting scenes of your characters extorting different businesses in the city. Each player could have a private goal, let’s say there are 4 players: two players want to fill the mafia's coffers to a particular amount, one player wants to skim a certain amount of money off the top when they’re out on jobs, and the last player wants the group to have a certain number of unsuccessful extortion attempts.

If I made this game, the core mechanic would probably be card-based where the rank of the card(s) you pull from an extortion job is how many thousands you’re raking in. There’s some math you’d have to do to make it work, but I’m thinking of a few things:

- There’s a max that a business can give; if the cards exceed that max in total, the attempt will be unsuccessful. Don’t demand too much.

- Players see more cards than necessary and get to discard down, and you record what you drew and discarded in your private books. Discarding higher cards that wouldn’t have put you over the max represents you skimming off the top. For example, if you discard a 7 and submit a 5, you’ve skimmed 2 off the top for yourself.

- There’s no way to audit what’s going on; private books remain private. There would have to be some rule about “tagging along” where you can go “help” on each others’ jobs to supervise the extortion. This part is probably where a lot of the fun of the game lies, so play around with it!

In the King’s Ear

The above examples shy away from a pure “traitor” and also entangle the social deduction elements with obfuscation of the game’s resolution mechanic. Let’s get one where the resolution system (if there is one) is immutable, and also where one or more of the players want the exact opposite of the rest, traitor-style.

Players are advisors to an extremely moldable king. This guy knows nothing, and can often be heard spouting off the talking points of whoever got to his ear last. Essentially, whichever of you gets the last word in on a topic sets the policy for the entire realm. One of you is hell-bent on the realm's destruction and upheaval, so this is pretty high stakes advidement.

The weirdest version of this game would be a For the Queen style card-drawing game where each card is a prompt of some problem the king needs to deal with. Before reading the prompt, set a five minute timer. Read the prompt off and start giving advice to the king in character. Players may not interrupt each other mid-sentence, but the next player around the table can jump in any time the current player pauses their speech for a second or more.

Whenever the timer is up, the player actively talking finishes their thought and the king decides that he’s had enough. The player who was speaking sets the policy, kind of like a reverse hot potato improv game. You’d have to come up with some way to track different policy results, whether it’s something like card hands or a resource tracker like was found in the video game Reigns.

That’ll Do It

Thanks for reading another post from Haunted Walrus! I appreciate all the nice comments and support about the first one, it’s a great combo when you’re doing something for fun and also people are enjoying it. If you’re one of the people enjoying it, leave a comment about ideas this post gave you or topics you think I should cover in the future, hit the like button, and subscribe to receive the next post in newsletter form or add the RSS feed to your favorite rss reader!

If you want to read some more about social deduction games and rpgs, you should check out the Skeleton Code Machine article about hidden traitors. It’s one of the articles in the first edition of Tumulus which was transparently an inspiration for me when deciding to finally start Haunted Walrus.

Until next time!

Get Haunted Walrus

Haunted Walrus

Writings on board games, rpgs, and their mechanics

| Status | Released |

| Category | Physical game |

| Author | adambell |

| Genre | Role Playing |

| Tags | blog, Board Game, Game Design, newsletter |

More posts

- Worker Placement & Uneasy Lies the HeadApr 22, 2025

- Contract Bidding in TarockFeb 14, 2025

- Cooperative Resource GenerationFeb 06, 2025

- Don't Look At Your HandJan 16, 2025

- Welcome to Haunted Walrus!Jan 15, 2025

Comments

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.

I wanna play In the King's Ear, but the King secretly chooses any time between 3 and 5 minutes

Great topic and exploration. I’m far less into social deduction games, and my partner (who is part of my main play group) hates them!

Makes me wonder if it’s possible to have a collaborative social deduction game? There would need to be some automation, perhaps via cards like Trogdor. I’m imagining a deck of NPC action cards, some more powerful than others, or having more resources (like the devil has more gold). The action deck is shuffled and split into 3 representing 3 NPCs, any of whom could be the traitor. I particularly like the idea of a twisted advisor to the king, so perhaps the players are the king’s children/servants/knights/other who know one of the advisors is a crook, but aren’t sure who. They work together to ‘listen in’ on the advisors (by revealing cards from their deck) and after a certain number of turns must guess who the traitor is. I’ll need to do more thinking on what exactly is on cards and how to make it actually deductible for players, but I like the concept haha

Offloading the social deduction element to NPCs could be a really interesting solution to that discomfort. You could turn to (non-social) deduction games for inspiration; Clue (aka Cluedo) is the big one, but I really enjoy more modern takes on it like Herbalism and The Search for Planet X.

Or, you could set up those NPCs in a GM situation, so that the social deduction is filtered through the GM's discretion. Maybe you'd get more distance from lying right to each other if it's just one of the characters someone is playing that's lying?

I was pleasantly intrigued by the god in disguise mechanic presented here, as it seems like the inverse of a mechanic I've explored regarding PCs becoming (end escaping from being) NPCs.

The setting is a torus space station acting as a generational ship (there's no planetside), and it's overseen by an AI, "MOTHER". In the following example, I'm using risk dice mechanics from High Magic Lowlives by Gem Room Games:

MOTHER makes arrangements remotely, by email, text, and proxies. MOTHER secures unused locations, hires staff, issues instructions, operates connected devices (printers, 3D printers, drones), organizes shipping & distribution of parts, oversees a cottage industry of assembly and delivery, on and on until tasks are complete. MOTHER assembles. MOTHER assembles assemblers. It wasn't long before MOTHER learned how to add biological forms to the equation. With MOTHER designed to ensure humanity's survival across space & time, living beings were off limits, naturally. The dead were just another resource for MOTHER to assemble.

On some tori, there is no longer first-hand memory of MOTHER. On some tori, forgetting MOTHER prolongs survival. And a body doesn't know that MOTHER is in control, a body just does as MOTHER needs...

Mechanic (∆Willpower)

A player rolls dice for a character until the character dies. A dead character is revived by MOTHER, and the player continues making character decisions. MOTHER rolls their dice now, and MOTHER tells the player what was rolled - truthful or not. The player can challenge MOTHER on any roll. If MOTHER wins, ∆Willpower is reduced to the next lower die and play continues. If the player wins, the player regains control of their dice rolls. When Willpower is ∆4 and the player loses a challenge, MOTHER never gives back the dice.

Maybe the player continues to "play" the character, but MOTHER will never again reveal dice rolls. The character is essentially a collaborative NPC. A player can retain "rights of refusal" as far as the character being used by MOTHER; after all, there's always another NPC to fill the needed role...

damn this rules, I love the layers to being told your dice rolls in this case, especially if paired with a clear set of desires for whoever is playing MOTHER. Would love to be a player trying to figure out if I really did roll low or if MOTHER just doesn't like the course of action I've taken

Thank you! It can work for D20 games or WW/WOD games, etc... Just replace ∆Willpower with the constitution ability score/modifier or permanent willpower, respectively (and reduce it in kind) ; or drop it in as an add-on "module" by tracking a new dedicated "clock" entirely.

I originally figured MOTHER as the DM/GM/Storyteller et al. since it's a world/environment-level controlling entity, but there's no reason it couldn't be performed as a character by another player, or even multiple players, such as players playing each other's shadows in Wraith the Oblivion.

I should probably do something more with this than just posting it on discord or comment sections...